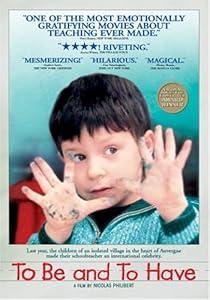

When I first heard that a French documentary film called Être et avoir (To be and to have) was turning out to be a great success, I was really surprised. A documentary named after two verbs! Seeing it would be like going back to the first dreadful days of school, surely. What next, a comedy about arithmetic and algebra! I had to see it out of curiosity (I am a former teacher) and of course the film, directed by Nicolas Philibert and set in a small rural school, was about a lot more than getting kids to conjugate two verbs correctly. If you have not seen it (it was released in 2002), I highly recommend it.

One thing we could learn from the film, in case you didn’t know already, is that the verb “to have” is as important as the verb “to be“. This is because in the Romance languages, as well as in English, to have is an auxiliary verb that helps form compound tenses (such as “I have eaten”). Furthermore, in some Romance languages the verb “to have” is often used in contexts where English would normally use the verb “to be” … for example, “I have thirst” rather than “I am thirsty”, and “I have 32 years” rather than “I am 32”. In the Romance languages to be and to have tend to be irregular verbs.

To have in French is avoir, in Italian it is avere, and in Romanian it is a avea. You can see the similarities. (Portuguese and Spanish are a little bit different, as usual – it seems their respective equivalents of this verb, haver and haber, now have limited use as an auxiliary verb and ter and tener are more commonly used, particularly to indicate possession, but let’s leave that for another post.)

Let’s look at their conjugations

I will put the singular persons on the top line and the plurals underneath, and the masculine form first in the third persons.

Language: first person second person third person

French j’ai tu as il a, elle a

French nous avons vous avez ils ont, elles ont

Italian io ho tu hai lui ha, lei ha

Italian noi abbiamo voi avete loro hanno

Romanian eu am tu ai el are, ea are

Romanian noi avem voi aveţi ei au, ele au

The negative form

is constructed thus (with a translation of “Maria has a dog” and “Maria does not have a dog” cited as an example):

- In French one usually puts a ne in front of the verb (or n’ if a vowel follows) and a pas after it: Maria a un chien. Maria n’a pas de chien

- In Italian one puts a non in front of the verb: Maria ha un cane. Maria non ha un cane.

- In Romanian one puts a nu in front of the verb: Maria are un câine. Maria nu are câine

In Romanian, the nu becomes n- in front of the a of an auxilary verb. For example, here is a song I like by a Romanian band, Holograf. The song is N-am stiut, which means I didn’t know. In this posting the lyrics have been translated on screen into Italian and English. It’s another song about lost love and regrets, and the accordion notes round about the 2:10 mark sound very French. Play it a few times and I expect you will be humming nu, nu, nu to yourself regularly.

The main thing with the verb ‘to have’, I guess, is to have fun 🙂

0 comment

[…] this post is the follow-up to the one looking at the verb “to have” in the other three of my five Romance languages (luckily I stopped at five, methinks). Unlike French, Italian and Romanian, both Spanish and […]