I have been reading The Shortest History of Europe, by John Hirst (published by Black Inc). It’s 147 pages long (short?), for those who are thinking of writing a shorter one and snatching the title from him. It’s really a series of lectures he gave at La Trobe University in Melbourne to introduce European history to university students in Australia, who apparently, “had had too much Australian history and knew too little of the civilisation of which they are a part”. But it’s a good refresher for anyone who wants a very general look at how Europe came to be what it is today. The book has had quite a few front covers but mine looks like the one in the picture, from 2009. Since then, I think, it has been reprinted with more dramatic covers, and possibly even updated.

I have been reading The Shortest History of Europe, by John Hirst (published by Black Inc). It’s 147 pages long (short?), for those who are thinking of writing a shorter one and snatching the title from him. It’s really a series of lectures he gave at La Trobe University in Melbourne to introduce European history to university students in Australia, who apparently, “had had too much Australian history and knew too little of the civilisation of which they are a part”. But it’s a good refresher for anyone who wants a very general look at how Europe came to be what it is today. The book has had quite a few front covers but mine looks like the one in the picture, from 2009. Since then, I think, it has been reprinted with more dramatic covers, and possibly even updated.

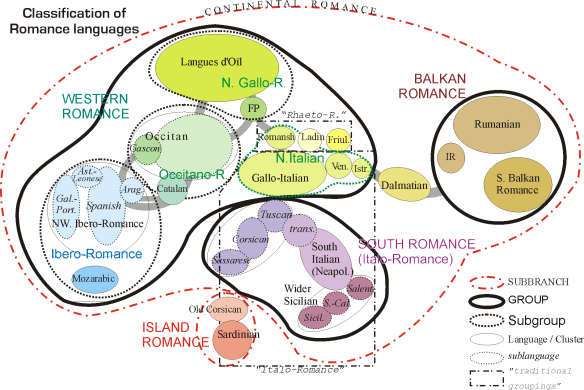

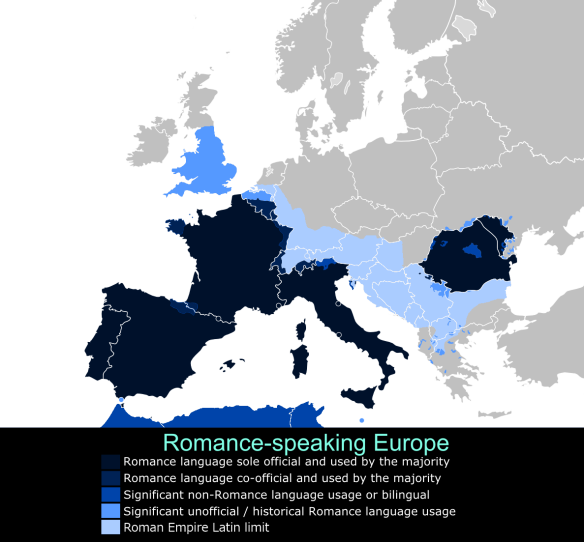

It includes an excellent chapter on languages, which has certainly given me a clearer picture of the overall set-up, whereas often those complicated graphs, charts or family trees that you see in reference books and websites leave you feeling more bewildered than anything else. The chapter starts off by explaining how there were two “universal languages” in the Roman empire, Latin in the west and Greek in the east, and the boundary between the west and east ran through what is now part of Serbia. But even though the Romans got as far west as Britain, there the Celtic language survived. In contrast, in the rest of the west, many of what were the local tribal languages, if you like, gave way to Latin. Not the formal Latin of scholars, but rather the “vulgar” Latin spoken by soldiers, traders and the like. There were, of course, regional variations, and after the Roman empire broke up, these evolved into separate languages, the Romance languages. Hirst says the chief Romance languages are French, Spanish and Italian, but I think the Portuguese and Brazilians would quibble with that.

Latin, Hirst says, was a highly inflected language – that is, “the meaning of a word in a sentence depends on the ending of the word (its inflection)” and word order in Latin “does not matter”. He then explains that people, through ignorance of the grammatical rules, began to use prepositions and did not change the word ending. This, he says, “explains why Romance languages do not inflect their nouns and hence word order is crucial”. (But Romanian, for example, still has some characteristics of Latin that the other Romance languages don’t).

There is also an interesting segment on how Latin did not have a word for “the“, so people used the demonstrative pronoun “that” (ille in the masculine form, illa in the feminine), which were shortened to le and la in French, el and la in Spanish and il and la in Italian. (In Portuguese, o and a are used, but in Romanian, “the” is a suffix attached to the end of the word).

In the fifth century, the Roman empire fell, not so much in a significant battle but more by petering out – it just became too hard to administer from a central point – and German conquerors took over in the west, while in the sixth and seventh centuries, Hirst says, the Slavs settled into much of what was the eastern part of the old Roman empire. However, the Romance languages survived in south-western Europe because Germanic settlement there was not strong enough to change the languages, but it did add Germanic words to the local Romance lexicons. These words were mainly, Hirst says, “those concerned with kings and government and with the feudal system; that is, the terminology of the new ruling class”. Later, of course, France, Spain and Portugal evolved into powers in their own right, and so cemented their languages.

However, as the above map shows, Germanic languages are prevalent today in the western-central parts of Europe, in most of Scandinavia and in Ireland and Britain. The history of England and hence English is interesting. Hirst says, “It is in England that the Germanic languages had a complete victory, which is to be expected given the over-running of the Britons by the invading Angles, Saxons and Jutes.” Later, in the ninth and tenth centuries, England was again invaded by Germanic-speaking tribes – Norsemen and Danes. “The basic vocabulary of English emerged with the melding of these Germanic tongues. In the process English lost the inflections of its Germanic origins,” Hirst writes. Then in 1066 England was invaded by the Normans, who spoke a variant of French. “England’s new ruling class continued to speak Norman French for several centuries until this too was melded into English, which resulted in a huge increase in the vocabulary of English. There were now two or more words for almost everything.” (Hirst gives the examples of royal, regal and sovereign being added to king and kingly.) This may explain why English is a challenging and perhaps baffling language for other language speakers to learn! (My comment, not Hirst’s.)

Hirst does point out that the Latin/Romance, Greek, Germanic and Slavonic languages are descended from what has been called the Indo-European language. It has been given that name “because the Indian language Sanskrit and Iranian are also descended from it”. But, Hirst says, linguists are still arguing or debating over where the Indo-Europeans lived. The discovery of the Indo-European language is attributed to William Jones (1746-1794), an English judge living in India, but others also contributed, some of them before Jones did.

But not all European languages belong in this category – some European languages are what Hirst calls “loners” – they are not closely related to any other. Greek and Albanian are among them, even though they are Indo-European. Hungarian and Finnish are not Indo-European, and neither is Basque (no-one quite knows where it comes from”).

So why is Romanian the “surprise” sole surviving Romance language in the former eastern part of the old Roman empire (the lonely black blob on the right in the above map)? Romania today is sandwiched between Slavic-language speaking Ukraine to the north and east (as is Romanian-speaking Moldova) and by Slavic Bulgaria and Serbia to the south and south-west. Hungary, too, is an odd meat in a similar Slavic sandwich. How come the Slavs did not make their linguistic presence felt in this region? Hirst does not go into this much, other than to say, “That country [Romania] lies to the north of the River Danube, which was usually the border of the Roman Empire. The Romans extended their control north of the river in a great bulge for a hundred years but that would not seem a long enough exposure to Latin for it to have become the base for Romanian. This has led to the suggestion that the Romanians lived south of the river, where they had a long exposure to Latin, and later moved north, not a suggestion that the Romanians are happy with.” (A reference, most probably, to territorial disputes with Hungary and arguments over whose ancestors were there first, etc). I think it would need a much longer history of Europe, of the Slavs, of the Dacians, and the Turks, and of Romania in particular, to be able to answer that properly. I’ll get back to you later, okay? Much later, probably!

* John Hirst’s books are available online at the Black Inc website. Here is the link to The Shortest History of Europe, which appears to be available as an e-book too. I bought mine in a second-hand bookstore.

* Language maps and illustrations from Wikipedia.

Related articles

- Let’s get a little vulgar and wax lyrical but not with earwax please

- Useful expressions in Romanian, like oral sex tomorrow, perhaps

- The quirks of Romania (and Romanian)

- Being Romanian gets the knees up and tongues wagging

- Limba up for the limba română

- Do your head in with the rudiments of Romanian

- Being Italian: is your ego under control?

- Start flying in Italian, sort of

- Doors are dumb asses, really

- Let’s chat up French people and have fat mornings

- Some basic French: nouns and articles (les noms et les articles)

- Being French… étant français

- The haves and have nots in French, Italian and Romanian

- Is Portuguese ready to steal the limelight?

- Newsroom blooper: In Brazil they speak Spanish, don’t they? No, Italian. What a cock-up!

- Get a grip on masculine and feminine forms in Portuguese

- Being Portuguese … sendo Português … is complicated

- Being Spanish means giving the vocal cords a good workout

- The burgers are better when they are hamburguesas

- Let’s chat up a few million Spaniards and have nice days

- Talk like a drunk and you’ll be fine

5 comments

World history …. think i prefer Bill Bryceland. Lighthearted & some info somewhere i guess …. just realised that my brain has turned to mush!

Abbreviated history! Not even of the world, just one continent haha.

I think I need to read this 🙂

It’s a bit long, despite the title! Enjoy your travels near “the Rock”.

How ironic, lol.

I’m in love with The Rock…